|

|

|

|

|

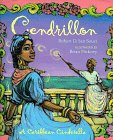

San Souci, Robert D. 1998. Cendrillon. Ill. by Brian Pinkney. New York: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. ISBN: 0-689-80668-X.

Robert San Souci and Brian Pinkney's Caribbean Cinderella variation is one that will not only engage children, but will accurately introduce them to the French Creole dialect. While there are many adaptations of the Cinderella story, San Souci and Pinkney collaborate to make this lively story particularly vibrant, both in language and in illustration.

The variant, which San Souci explains in his author's note as being "loosely based on the French Creole tale 'Cendrillon' in Turiault's nineteenth century Creole Grammar," is told from the point of view of the orphaned godmother who inherited a magic wand from her mother upon her death. The godmother is a laborer who is bestowed godmother by an employer who ultimately dies. Sticking to the traditional Cinderella story, upon the remarriage of Cendrillon's father, Cendrillon becomes the stepdaughter who is forced to labor for her wicked stepmother while her stepsister is showered with affection and placed on a pedestal.

Upon learning about a birthday ball for a handsome prince-like fellow, the godmother who is forever watching out for Cendrillon decides to put her wand to work at last. San Souci's godmother, however, turns a fruit à pain, or breadfruit, into a coach; field lizards into footmen; and agoutis (rodents) into horses. Pinkney's scratchboard illustrations give the story a lively feeling and as Ilene Cooper notes, the "pinks, greens, and blues" evoke "the warm breezes of the islands" (1998). The illustrations beautifully suggest the setting and move the story along with their portrayals of action. Pinkney uses swirls to depict movement. From the waving of the magic wand to the rotation of the carriage wheels, the reader is propelled along subconsciously.

Flowers, rags, shoes, stars, or native plant life frame some of the pages, further adding to the setting. Pinkney's ability to portray the characters' emotions and personalities shines, from the cover, which features an innocent, happy Cendrillon, to the horror and exasperation of the wicked stepsister and stepmother when the shoe doesn't fit. The pictures are well integrated with the text of the story.

The text too, is rich and vivacious.San Souci's introduction of French Creole grammar into the work gives it an authentic touch. The dialogue is realistic and portrays well the intimate relationship that Cendrillon shares with her godmother. For instance, as she is wavering on going to try on the shoes when Paul comes to her home, her godmother tells Cendrillon, "Now, child, if you love me"..."do this one thing for me: Go out into the hall." Further, San Souci's precise vocabulary leaves no room for the reader to wonder about his characters' intent or actions. Although the pictures do a wonderful job of telling the story, phrases such as "his eyes blazing with love fire" create brilliant imagery.

San Souci and Pinkney's Cendrillon is a wonderful rendition of an all-time favorite which will introduce children to a beautiful new world.

1998. Cooper, Ilene. Review: Cendrillon by San Souci, Robert D. Illus. by Pinkney, Brian. Booklist 95 (15 October). Available from http://archive.ala.org/booklist/v95/youth/oc2/62sansou.html. Accessed 01 February 2004.

|

|

|

Schwartz, Alvin. 1992. And the Green Grass Grew All Around: Folk Poetry From Everyone. Ill. by Sue Truesdell. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN: 0-06-022757-5.

Schwartz's collection of folk poems is full of well-loved favorites as well as new verses that children will delight in. Schwartz has put together a spirited compilation, including jeers, jump rope poems, nursery rhyme parodies, scary poems, and silly chants amongst others.

This carefully selected anthology is fun, plain and simple. Although some of the variants are tongue twisters, there is a good oral quality to the verses Schwartz chose. The language invites participation. It is musical and one cannot help but try to sing along as he/she reads the verses. Readers will be pleased to find some familiar verses as well as variants of those that they are familiar with.

Sue Truesdell's illustrations are a perfect companion for Schwartz's nonsense. The watercolor and pen drawings feature a cast of wide-eyed characters embroiled in non-stop mayhem. Although they are in black and white, they add a great deal of color to the book. No matter how dark the accompanying poem, the lively illustrations keep the tone of the book upbeat. The poem Titanic, which finishes, "It was Sad, it was sad; It was sad when the great ship went down; To the bottom of the--; Husbands and wives, Little children lost their lives. It was sad when the great ship went down, Went down." Yet the accompanying illustration featuring an animated old sailor telling the tale to a bug-eyed boy, girl, and a cat sitting on a barrel keep the mood from turning morose.

Musical scores accompany some of the verses. However, perhaps the most interesting features are the bibliography, the well-researched historical commentary, and an index of first lines. Schwartz's notes are easy enough for children to follow, but provide an in-depth look at the history behind folk poetry that is informative enough for adult research. Readers of all ages will be sure to sing along to Schwartz's zany collection and will likely be inspired to concoct a few lines of their own.

Scieszka, Jon. 1991. The Frog Prince Continued. Ill. By Steve Johnson. New York: Viking. ISBN: 0-670-83421-1

Ever wonder what happens to fairy tale characters after they live happily ever after? Jon Scieszka and Steve Johnson deliver a hilarious answer to the question every child wonders about. "Well, let's just say they lived sort of happily for a long time. Okay, so they weren't so happy. In fact, they were miserable." The princess complains about the Prince's croaking snore and he complains that she never wants to visit the pond anymore. Unsettled, the Frog Prince sets out to be turned back into a frog and the readers come across a host of situations which they will feel they have seen somewhere before.

In his search for a witch who can revert him back to a frog, the prince encounters three witches who are fixating over their own fairy tales--one ensuring that a handsome prince doesn't wake Sleeping Beauty, another that Snow White isn't rescued, or still another that the guests arrive for dinner at her gingerbread house. Finally, the Prince meets up with a "Fairy Godmother" who inadvertently turns him into a carriage before he realizes that life with the princess is not so bad after all.

Children will delight in Scieszka's dialogue and wit. When the Prince comes across the third witch, she cuts him off to reply, "If you're a frog, I'm the King of France." Although the story is technically not traditional literature, it contains many elements that are found in works of traditional fantasy. The plot is very simple. It involves an opening, a quest, and a quickly developed resolution. Most noticeably, however, is the repetition of elements--the Prince keeps encountering witches who aren't the witch he is looking for. Each witch tells him that he does not look like a frog. Finally, as with all good traditional fantasy, there is a happy ending.

While the language is simplistic, the use of illustrations to extend the plot allows children to guess what will happen next. Steve Johnson's dark, surreal illustrations give the story a dismal tone, accurately setting the mood. The illustrations almost enable one to feel the cold, lonely feeling of being in the forest alone at night, forced to rethink one's decisions. As Linda Boyles said in her review, "they are filled with subtle and surprising humor that continually rewards viewers with laugh-out-loud visual treats. The overall design is clean and spacious, with figures and objects moving past the ragged borders of the pictures and across the pages, matching the verbal movement perfectly" (1991). While it might not be a classic, the book is a fine example of Scieszka's original and hilarious work and will serve to encourage others to fracture classic tales.

Boyles, Linda. 1991. Review: The Frog Prince Continued. School Library Journal. (May). In Bowker's Books in Print (database online). Available from http://www.booksinprint.com/bip/. Accessed 03 February 2004.

|

|

|

|

|

|